Women in World War Two

As in World War One, women played a vital part in this country’s success in World War Two. But, as withWorld War One, women at the end of World War Two, found that the advances they had made were greatly reduced when the soldiers returned from fighting abroad.

At the end of World War Two, those women

who had found alternate employment from the normal for women, lost their

jobs. The returning soldiers had to be found jobs and many wanted

society to return to normal. Therefore by 1939, many young girls found

employment in domestic service – 2 million of them, just as had happened

in 1914. Wages were still only 25p a week.

When women found employment in the Civil Service, in teaching and in medicine they had to leave when they got married.

However, between the wars, they had got

full voting equality with men when in 1928 a law was passed which stated

that any person over the age of 21 could vote – male and female.

The war once again gave women the opportunity to show what they could do.

Evacuation:

Young mothers with young children were

evacuated from the cities considered to be in danger. In all, 3.5

million children were evacuated though many went with a teacher. As

young children were normally taught by females, many of those who went

with the children were women. The fact that women were seen to be the

people who taught the youngest was something that had been going on for

years.

The Women’s Land Army:

As in World War One, women were called on

to help on the land and the Women’s Land Army (WLA) was re-formed in

July 1939. Their work was vital as so many men were being called up into

the military.

| www.afomicworld.blogspot.com |

In August 1940, only 7,000 women had joined but with the crisis caused by Hitler’s U-boats,

a huge drive went on from this date on to get more women working on the

land. Even Churchill feared that the chaos caused by the U-boats to our

supplies from America would starve out Britain.

The government tried to make out that the

work of the WLA was glamorous and adverts showed it as this. In fact,

the work was hard and young women usually worked in isolated

communities. Many lived in years old farm workers cottages without

running water, electricity or gas. Winter, in particular, could be hard

especially as the women had to break up the soil by hand ready for

sowing. However, many of the women ate well as there was a plentiful

supply of wild animals in the countryside – rabbit, hares, pheasant and

partridges. They were paid 32 shillings a week – about £1.60.

In 1943, the shortage of women in the

factories and on land lead to the government stopping women joining the

armed forces. They were given a choice of either working on the land or

in factories. Those who worked on land did a very valuable job for the

British people.

Factory Work:

Many women decided that they would work in

a factory. They worked in all manner of production ranging from making

ammunition to uniforms to aeroplanes. The hours they worked were long

and some women had to move to where the factories were. Those who moved

away were paid more.

Skilled women could earn £2.15 a week. To

them this must have seemed a lot. But men doing the same work were paid

more. In fact, it was not unknown for unskilled men to get more money

that skilled female workers. This clearly was not acceptable and in

1943, women at the Rolls Royce factory in Glasgow went on strike. This

was seen as being highly unpatriotic in time of war and when the female

strikers went on a street demonstration in Glasgow, they were pelted

with eggs and tomatoes (presumably rotten and inedible as rationing was

still in) but the protesters soon stopped when they found out how little

the women were being paid .The women had a part-victory as they

returned to work on the pay of a male semi-skilled worker – not the

level of a male skilled worker but better than before the strike.

The Women’s Voluntary Service (WVS):

During the Blitz on London women in

voluntary organisations did a very important job. The Women’s Voluntary

Service provided fire fighters with tea and refreshments when the

clear-up took place after a bombing raid. The WVS had one million

members by 1943. Most were quite elderly as the younger women were in

the factories or working on farms and were too exhausted to do extra

work once they had finished their shift. The WVS also provided tea and

refreshments for those who sheltered in the Underground in London.

Basically, the WVS did whatever was needed. In Portsmouth, they

collected enough scrap metal to fill four railway carriages……..in just

one month. They also looked after people who had lost their homes from

Germans bombing – the support they provided for these shocked people who

had lost everything was incalculable. When the WVS were not on call,

they knitted socks, balaclavas etc. for service men. Some WVS groups

adopted a sailor to provide him with warm knitted clothing.

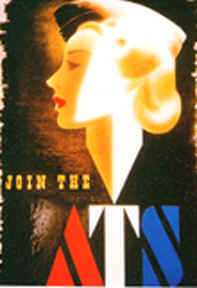

The Auxiliary Territorial Service:

In the military, all three services were

open for women to join – the army, air force and navy. Women were also

appointed as air raid wardens.

In the army, women joined the Auxiliary

Territorial Service (ATS). Like soldiers, they wore a khaki uniform. The

recruiting posters were glamorous – some were considered too glamorous

by Winston Churchill – and many young ladies joined the ATS because they

believed they would lead a life of glamour. They were to be

disappointed. Members of the ATS did not get the glamour jobs – they

acted as drivers, worked in mess halls where many had to peel potatoes,

acted a cleaners and they worked on anti-aircraft guns. But an order by

Winston Churchill forbade ATS ladies from actually firing an AA gun as

he felt that they would not be able to cope with the knowledge that they

might have shot down and killed young German men. His attitude was odd

as ATS ladies were allowed to track a plane, fuse the shells and be

there when the firing cord was pulled……By July 1942, the ATS had 217,000

women in it. As the war dragged on, women in the ATS were allowed to do

more exciting jobs such as become welders (unheard of in ‘civvie’

street), carpenters, electricians etc.

The recruiting poster for the ATS banned by Churchill

|

The Women’s Auxiliary Air Force:

Women who joined the Royal Air Force were

in the Women’s Auxiliary Air Force (WAAF). They did the same as the ATS

(cooking, clerical work etc) but the opportunities were there for

slightly more exciting work. Some got to work on Spitfires. Others were

used in the new radar stations used to track incoming enemy bomber

formations. These radar sites were usually the first target for Stuka

dive-bombers so a post in one of these radar stations could be very

dangerous. However, the women in this units were to be the early warning

ears and eyes of the RAF during the Battle of Britain. For all of this,

women were not allowed to train to be pilots of war planes. Some were

members of the Air Transport Auxiliary (ATA) which flew RAF planes from a

factory to a fighter squadron’s base. There were 120 women in this unit

out of 820 pilots in total. The women had fewer crashes than male

pilots but they were not welcome as the editor of the magazine

“Aeroplane” made clear : they (women ATA) “do not have the intelligence

to scrub the floor of a hospital properly.” He , C.G. Grey, claimed that

they were a “menace” when flying.

Secret Agents:

Women were also used as secret agents.

They were members of SOE (Special Operations Executive) and were usually

parachuted into occupied France or landed in special Lysander planes.

Their work was exceptionally dangerous as just one slip could lead to

capture, torture and death. Their work was to find out all that they

could to support the Allies for the planned landings in Normandy in June

1944. The most famous female SOE members were Violette Szabo and Odette

Churchill. Both were awarded the George Cross for the work they did –

the George Cross is the highest bravery award that a civilian can get.

Both were captured and tortured. Violette Szabo was murdered by the

Gestapo while Odette Churchill survived the war.

Entertainment:

Women were also extremely important in

entertainment. The two most famous female entertainers during the war

were Vera Lynn (now Dame Vera Lynn) and Gracie Fields. Vera Lynn’s

singing (“There’ll be blue birds over the White Cliffs of Dover” and

“We’ll meet again, don’t know where, don’t know when”) brought great

happiness to many in Britain. She was known as the “Forces Sweetheart”.

Gracie Fields was another favourite with the forces.

1945:

The war in Europe ended in May 1945. At

this time there were 460,000 women in the military and over 6.5 million

in civilian war work. Without their contribution, our war effort would

have been severely weakened and it is probable that we would not have

been able to fight to our greatest might without the input from women.

Ironically, in Nazi Germany, Hitler had forbidden German women to work

in German weapons factories as he felt that a woman’s place was at home.

His most senior industry advisor, Albert Speer, pleaded with Hitler to

let him use German female workers but right up to the end, Hitler

refused. Hitler was happy for captured foreign women to work as slaves

in his war factories but not German. Many of these slave workers, male

and female, deliberately sabotaged the work that they did – so in their

own way they helped the war effort of the Allies.

While in America

During World War II, some 350,000 women served in the U.S. Armed Forces,

both at home and abroad. They included the Women’s Airforce Service

Pilots, who on March 10, 2010, were awarded the prestigious

Congressional Gold Medal. Meanwhile, widespread male enlistment left

gaping holes in the industrial labor force. Between 1940 and 1945, the

female percentage of the U.S. workforce increased from 27 percent to

nearly 37 percent, and by 1945 nearly one out of every four married

women worked outside the home.

Women in the Armed Forces

In addition to factory work and other home front jobs, some 350,000 women joined the Armed Services, serving at home and abroad. At the urging of First Lady Eleanor Roosevelt and women’s groups, and impressed by the British use of women in service, General George Marshall supported the idea of introducing a women’s service branch into the Army. In May 1942, Congress instituted the Women’s Auxiliary Army Corps, later upgraded to the Women’s Army Corps, which had full military status. Its members, known as WACs, worked in more than 200 non-combatant jobs stateside and in every theater of the war. By 1945, there were more than 100,000 WACs and 6,000 female officers. In the Navy, members of Women Accepted for Volunteer Emergency Service (WAVES) held the same status as naval reservists and provided support stateside. The Coast Guard and Marine Corps soon followed suit, though in smaller numbers.One of the lesser-known roles women played in the war effort was provided by the Women’s Airforce Service Pilots, or WASPs. These women, each of whom had already obtained their pilot’s license prior to service, became the first women to fly American military aircraft. They ferried planes from factories to bases, transporting cargo and participating in simulation strafing and target missions, accumulating more than 60 million miles in flight distances and freeing thousands of male U.S. pilots for active duty in World War II. More than 1,000 WASPs served, and 38 of them lost their lives during the war. Considered civil service employees and without official military status, these fallen WASPs were granted no military honors or benefits, and it wasn’t until 1977 that the WASPs received full military status. On March 10, 2010, at a ceremony in the Capitol, the WASPS received the Congressional Gold Medal, one of the highest civilian honors. More than 200 former pilots attended the event, many wearing their World War II-era uniforms.

“Rosie the Riveter”

While women worked in a variety of positions previously closed to

them, the aviation industry saw the greatest increase in female workers.

More than 310,000 women worked in the U.S. aircraft industry in 1943,

representing 65 percent of the industry’s total workforce (compared to

just 1 percent in the pre-war years). The munitions industry also

heavily recruited women workers, as represented by the U.S. government’s

“Rosie the Riveter” propaganda campaign. Based in small part on a

real-life munitions worker, but primarily a fictitious character, the

strong, bandanna-clad Rosie became one of the most successful

recruitment tools in American history, and the most iconic image of

working women during World War II.

In movies, newspapers, posters, photographs, articles and even a Norman Rockwell-painted Saturday Evening Post cover, the Rosie the Riveter campaign stressed the patriotic need for women to enter the work force—and they did, in huge numbers. Though women were crucial to the war effort, their pay continued to lag far behind their male counterparts: Female workers rarely earned more than 50 percent of male wages.

The Revolution

The Civil War

The Civil War

In movies, newspapers, posters, photographs, articles and even a Norman Rockwell-painted Saturday Evening Post cover, the Rosie the Riveter campaign stressed the patriotic need for women to enter the work force—and they did, in huge numbers. Though women were crucial to the war effort, their pay continued to lag far behind their male counterparts: Female workers rarely earned more than 50 percent of male wages.

The Revolution

The Revolutionary War saw many women marching off to war alongside their husbands. One of those was Margaret Corbin.

When her artilleryman husband was killed at the Battle of Fort

Washington, Margaret took his place on the firing line. For the rest of

the battle, she “manned” his cannon, firing continuously while being hit

in the arm, chest, and face.

Hundreds of women fought in this conflict, most of them disguised as men. One of them was Mary Galloway

who, at sixteen years old, took a bullet in the neck at Antietam. She

lay in a ditch for a day and half, refused treatment from male surgeons,

and was finally saved by another pioneering woman, Clara Barton.

Cathay Williams, born a slave, was freed by the Union Army and pressed into service as a cook, traveling with the 8th

Indiana through the Red River Campaign and the Battle of Pea Ridge. She

would go on to wear the Army’s blue uniform after the war, when,

disguised as a man, she enlisted and became the first female Buffalo

Soldier (that we know of!).

World Wars I and II

The twentieth century saw us stepping

onto the world stage, but we did so from behind the safety of two

oceans. That safety allowed the luxury of sexism. We didn’t deploy women

in direct combat roles because we didn’t have to. Other countries

didn’t have a choice. The most notable example in those two global

conflicts was Mother Russia, who called on her daughters to save her.

In World War I, when the Russian army was

crumbling, women stepped forward to fill the growing void. One of the

new all-female units was known as the “Battalion of Death,” the members of which not only stood their ground under fire, but shamed their male comrades by charging past them into battle.

By World War II, women filled every combat assignment in the Red Army. There were tankers, like Mariya Oktyabrskaya, who would jump out of her T-34 to repair it under fire. There were fighter aces like Lydia Litvyak, the “White Lily of Stalingrad” who shot down a dozen Nazi aircraft. And there were snipers like Lyudmila Pavlichenko who scored 309 confirmed kills, more than any American sniper in any war!

Vietnam

While women weren’t officially allowed in

direct combat roles, anyone wearing a combat action badge will tell you

that there is no safe zone in a guerilla war. More than 11,000 women

served in Vietnam. Some made history, like the US Navy’s Cdr. Elizabeth Barrett, who became the first female line officer to hold a command position in a combat zone. Some paid the ultimate price, like 1st Lt. Sharon Ann Lane, who was killed when her hospital was attacked by the Vietcong.

Today

Right now, half a world away, thousands of women are fighting ISIS as members of the YPJ, the Kurdish Women’s Defense Units.

They are serving in the kind of sustained land war Americans haven’t

seen since Korea. Make no mistake, these are frontline combat units, and

they know what will happen if they’re captured. And yet, as one of them

told the BBC, “One of our Women is worth 100 of their men.”

The Kurdish fighters facing off against ISIS clearly recognize the

valuable contributions women among their ranks have to make. It’s time

to make sure the American cultural narrative about women in direct

combat roles reflects these contributions, too—both current and

historical. Seeing depictions of women in combat action is an important

step toward encouraging more women to join newly opened combat arms

branches. As Maj. Gen. Tammy Smith recently reminded her followers on Twitter, “If I can see it I can be it.” Hollywood isn’t the solution. But it can and should be part of it.

So women out there in the Military.

You are not there by mistake . Go out there and make history.

Tell gender segregation to go to hell.

Have a nice day ,

Oh yes . see what the Dahomey women too did during their wars.

ReplyDeletewomen are ferocious as soldiers indeed.